“To make the invisible more visible to others, is after all, a major goal of the interpreter”

(Denzin 2010: 32).

A blog post from Susanne Kean. The University of Edinburgh.

Mapping or modelling is one way of making the invisible more visible to the researcher and, eventually, to the reader of research. Mapping or modelling are data analysis techniques that come into play after the first round of analysis. These techniques can be used independent of methodology. To explain this technique, I will draw on Thematic Analysis (TA) and coding.

Coding, of course, is only one way of analysing data and not THE way. Coding originates in Grounded Theory but is today used well beyond this methodology. TA is an example where coding is used as an analytical device. A code, Saldaña (2021) proposes, “is most often a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, saline, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data” (p5). In other words, it is shorthand for data content, and this could be a word or a line or a paragraph.

Now, coding is only the beginning of data analysis, and yes, coding is analysis. In conversations with others (and specifically research students), I often get the impression that coding is thought of as a mechanistic devise to somehow sort data. However, how we sort data demands thinking and analysis. Coffey and Atkinson capture this beautifully when they remind us that:

“First, coding links different segments or instances in the data. We bring those fragments of data together to create categories of data that we define as having some common property or element. The coding thus links all those data fragments to a particular idea or concept.

The important analytic work lies in establishing and thinking about such linkages, not in the mundane process of coding.

We use the data to think with, in order to generate ideas that are thoroughly and precisely related to our data. Coding can be thought about as a way of relating our data to our ideas about those data.

In practice, coding can be thought of as a range of approaches that aid organization, retrieval, and interpretation of data” (Coffey & Atkinson 1996:27).

Coding, and thus analysis of data, is an iterative process. I am a Grounded Theorist by training and background and so am very familiar with the cycles of coding from open coding to focused coding to developing categories and eventually one or two core categories. A core category is nothing more, or less, than the main story in a data set. Whether we call this a core category, or a theme is neither here nor there but simply a differed terminology depending on the approach one takes. In TA, this would be called a theme. My point here is that coding, and thus analysis, evolves from a descriptive level to an abstract level of analysis. I agree with Thorne (2020) when she highlights that “finding themes” is too often declared as the end product of analysis when in reality, this is reflects nothing more than “surface-level considerations” of any given data set. I am wary when I review articles where authors claim they found seven themes and 15 sub-themes. This more often than not indicates nothing more than a data analysis that stopped at this surface-level describing data but not analysing them.

Analysis, as Flick points out “can be oriented to various aims. The first such aim may be to describe a phenomenon. Or the analysis could focus on comparing several cases (individual or groups) and on what they have in common, or on the differences between them. The second aim may be to identify conditions on which such differences are based – which means looking for explanations for such differences. The third aim may be to develop a theory of the phenomenon under study from that analysis of empirical material” (Flick 2023:385, Italics in original).

There is, of course, nothing wrong with description and descriptive studies have their place. However, description remains on an inductive level of analysis, and this does not get us to themes. To truly develop themes, we need abduction as analytical process. It is this process that allows us to go beyond description to explanation and explore not only why somethings happens but also what is going on (Blaikie and Priest (2017).

One way of developing an analysis beyond descriptions is mapping for themes. This technique comes into paly after focused codes have been developed. So, not right at the beginning but at a stage where the analysist is thinking about the linkages between different codes and categories to develop themes. Saldaña (2021) describes different ways one can develop themes through mapping. He distinguished between (1) theming data categorically and (2) theming data phenomenologically. I usually have the first approach of developing themes in mind when using modelling or mapping as a technique. This approach to data analysis allows the analyst to go beyond the descriptive coding schemes and include theoretical ideas/ concepts as they apply to the data.

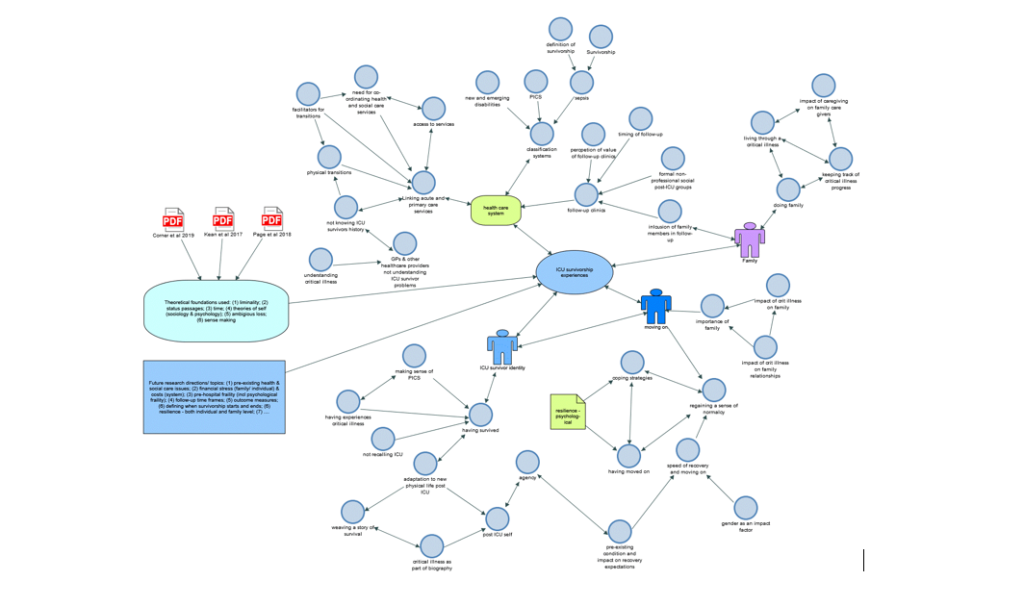

Here is an example where we used modelling in a systemtic review exploring intensive care survivorship experiences.

At this stage of the analysis, we were thinking about the linkages and hierarchies of theoretical concepts in our data set. Software packages, like NVivo, allow models to be “active” models, meaning one can play around with hierarchies and think through linkages with every change. Mapping alongside the developing analysis also functions as an audit trail of the data analysis and provides a structure for writing up at a later stage.

Analysis always requires the interaction with data, and this process of modeling allows the researcher to think theoretically about the data as well as deriving any ideas from the data because, as Atkinson (2015) argues “the end-point of analysis is not a knitting -together of coded themes” (p 62). It is this process that allows us to go beyond description to explanation and the process that too often is missing in much of qualitative work in nursing (Thorne 2020, Atkinson 2015).

In summary, mapping and modeling are data analysis techniques that are useful in developing analysis beyond description. These techniques help analysts to think through linkages of codes and hence the interpretation of data.

References:

Atkinson P (2015) For Ethnography, SAGE, London

Blaikie, N & Priest, J (2017) Social research – paradigms in action, polity

Coffey A & Atkinson P (1996) Making sense of qualitative data, SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Denzin N (2010) The qualitative manifesto. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek

Flick U (2023) An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 7th edition, SAGE, Los Angeles

Saldaña J (2021) The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 4th edition, SAGE, Los Angeles Thorne S (2020) Beyond theming: making qualitative studies count (editorial), Nursing Inquiry, 27: e12343, doi.org/10.1111/nin.12343