Author: Leena Salminen

Professor, Leader and coordinator of the project

University of Turku, Department of Nursing Science

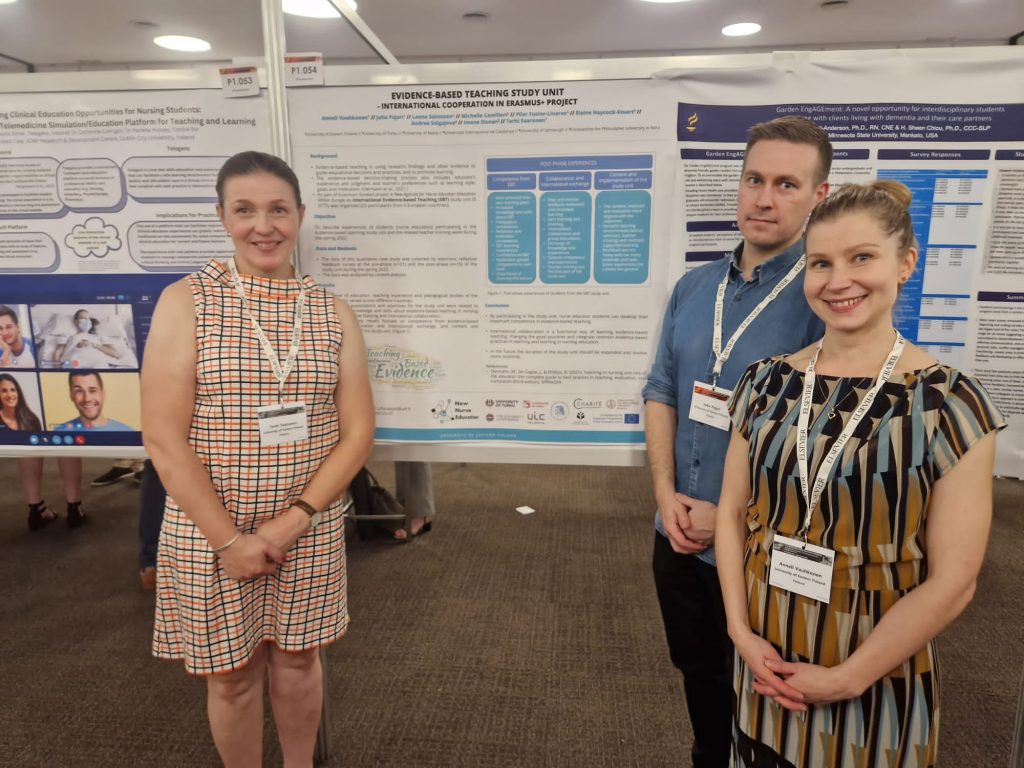

A New Agenda for Nurse Educator Education in Europe –project has ended in this Autumn. We can say, we have taken the first steps in harmonizing the nurse educator education within Europe. The results of our project are promising. The nurse educator programme (30 ECTS) conducted during the project was success and even more important, it was found to be an illustrative example of organizing the common European nurse education with varying teaching methods and modern contents. The learning outcomes were good, the students were satisfied with the programme even it was hard-working. All in all, the evaluated competence of nurse educators was at the good level (Elonen et al., 2023; Vauhkonen et al., 2024), but there is a need for systematic continuing professional development (Smith et al., 2023).

How did we do all this?

First of all, we had an amazing good and motivated project group. The group consisted of partners from five European countries (Finland, Malta, Scotland, Slovakia and Spain) and six universities (two from Finland). At the beginning of the project, we had partners also from German, but unfortunately, they withdraw the project for their organizational reasons. The

co-operation went very well all the time. Even we were all hurry, somehow all partners found the time to make this project. One of the reasons might be that this is so interesting and unique, never done before. The atmosphere in the group was open and discussing, and we supported each other. We also have fun!

Secondly, we had a quite good project plan done when applying the funding. We have prepared and written it together. We all agreed the aims and tasks planned to do during this project. It increased the commitment to the project. We had also planned “double cast” for every intellectual output and that way we ensured the tasks going on and get ready in time. Of course, we didn’t manage every task and the deadlines came too early but all in all, quite nicely.

Thirdly, we had time to make the project. This was three years EU funded project. This meant also that we have to prepare everything: tasks, responsibilities, schedule, and expected outcomes very carefully in time and beforehand. We had meetings at least every month, sometimes even often. It promoted our work.

Fourthly, we have a very good co-operation with the funder, and we were supported by our university concerning the financial things. Also, our National Erasmus Agency supported us and answered our questions quickly. We had strictly ruled with our partners concerning the financial things. It helped us to keep understanding the financial situation, how much we have money left and where we have spent it.

What could we have done better?

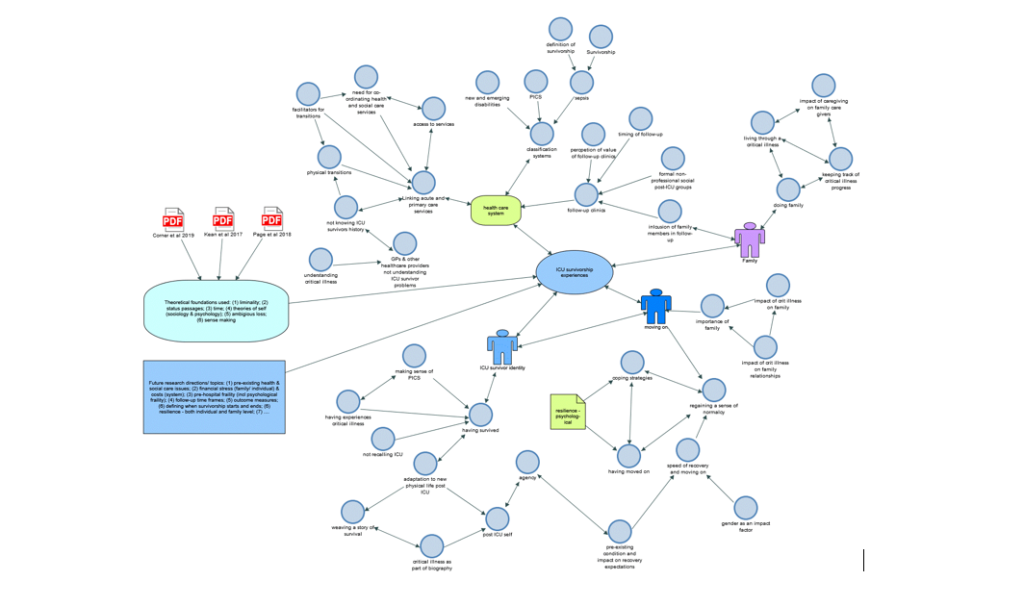

Of course, in every project there is something that to do better. We conducted quite much research during our project. One aim of this project was to set recommendations for future nurse educators’ qualifications and education, and we wanted it base on evidence. The research took time more time than we had estimated. It was not so easy to collect the data in five countries because they all have different kind of rules and legislation of research protocols.

The other thing we could have done better is sharing the knowledge we have produced. We have written many research articles, some of them are already published and some are still under review. You can follow our website to find the articles.

We need an agenda for nurse educator education

We need a new agenda for nurse educator education in Europe and it must be based on evidence. Only that way we can promote nurse educators’ qualification and competence. Nurse education needs excellent more than ever in this changing society and in emerging health care. Nurse educators have an important role implementing it. Only this way the patients can get the best care.

Merry Christmas

Finally, I want to thank all my project members for their hard, innovative and important work during the project. Without you, this has never been possible.

Also, I want to thank the funder, Erasmus+, giving possibility to conduct our project. This was our common dream, and we managed to do it.

I wish you all Merry Christmas and Prosperous New Year with the new projects.

References:

Elonen I, Kajander-Unkuri S, Cassar M, Wennberg-Capellades L, Kean S, Sollár T, Saaranen T, Pasanen M & Salminen L. 2023. Nurse Educator Competence in Four European Countries – A Comparative Cross-sectional Study. Nursing Open. 00, 1–12. DOI: 10.1002/nop2.2033

Smith J, Kean S, Vauhkonen A, Elonen I, Campos Silva S, Pajari J, Cassar M, Martin-Deldago L, Zrubcova D & Salminen L. 2023. An integrative review of the continuing professional development needs for nurse educators. Nurse Education Today. doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105695

Vauhkonen A, Saaranen T, Cassar M, Camilleri M, Martin-Delgado L, Haycock-Stuart E, Solgajová A, Elonen I, Pasanen M, Virtanen H & Salminen L. 2024. Professional Competence, Personal Occupational Well-Being, and Mental Workload of Nurse Educators – A Cross-Sectional Study in Four European Countries. Nurse Education Today 133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.106069