Category: Uncategorized

Author: Leena Salminen

Professor, Leader and coordinator of the project

University of Turku, Department of Nursing Science

A New Agenda for Nurse Educator Education in Europe –project has ended in this Autumn. We can say, we have taken the first steps in harmonizing the nurse educator education within Europe. The results of our project are promising. The nurse educator programme (30 ECTS) conducted during the project was success and even more important, it was found to be an illustrative example of organizing the common European nurse education with varying teaching methods and modern contents. The learning outcomes were good, the students were satisfied with the programme even it was hard-working. All in all, the evaluated competence of nurse educators was at the good level (Elonen et al., 2023; Vauhkonen et al., 2024), but there is a need for systematic continuing professional development (Smith et al., 2023).

How did we do all this?

First of all, we had an amazing good and motivated project group. The group consisted of partners from five European countries (Finland, Malta, Scotland, Slovakia and Spain) and six universities (two from Finland). At the beginning of the project, we had partners also from German, but unfortunately, they withdraw the project for their organizational reasons. The

co-operation went very well all the time. Even we were all hurry, somehow all partners found the time to make this project. One of the reasons might be that this is so interesting and unique, never done before. The atmosphere in the group was open and discussing, and we supported each other. We also have fun!

Secondly, we had a quite good project plan done when applying the funding. We have prepared and written it together. We all agreed the aims and tasks planned to do during this project. It increased the commitment to the project. We had also planned “double cast” for every intellectual output and that way we ensured the tasks going on and get ready in time. Of course, we didn’t manage every task and the deadlines came too early but all in all, quite nicely.

Thirdly, we had time to make the project. This was three years EU funded project. This meant also that we have to prepare everything: tasks, responsibilities, schedule, and expected outcomes very carefully in time and beforehand. We had meetings at least every month, sometimes even often. It promoted our work.

Fourthly, we have a very good co-operation with the funder, and we were supported by our university concerning the financial things. Also, our National Erasmus Agency supported us and answered our questions quickly. We had strictly ruled with our partners concerning the financial things. It helped us to keep understanding the financial situation, how much we have money left and where we have spent it.

What could we have done better?

Of course, in every project there is something that to do better. We conducted quite much research during our project. One aim of this project was to set recommendations for future nurse educators’ qualifications and education, and we wanted it base on evidence. The research took time more time than we had estimated. It was not so easy to collect the data in five countries because they all have different kind of rules and legislation of research protocols.

The other thing we could have done better is sharing the knowledge we have produced. We have written many research articles, some of them are already published and some are still under review. You can follow our website to find the articles.

We need an agenda for nurse educator education

We need a new agenda for nurse educator education in Europe and it must be based on evidence. Only that way we can promote nurse educators’ qualification and competence. Nurse education needs excellent more than ever in this changing society and in emerging health care. Nurse educators have an important role implementing it. Only this way the patients can get the best care.

Merry Christmas

Finally, I want to thank all my project members for their hard, innovative and important work during the project. Without you, this has never been possible.

Also, I want to thank the funder, Erasmus+, giving possibility to conduct our project. This was our common dream, and we managed to do it.

I wish you all Merry Christmas and Prosperous New Year with the new projects.

References:

Elonen I, Kajander-Unkuri S, Cassar M, Wennberg-Capellades L, Kean S, Sollár T, Saaranen T, Pasanen M & Salminen L. 2023. Nurse Educator Competence in Four European Countries – A Comparative Cross-sectional Study. Nursing Open. 00, 1–12. DOI: 10.1002/nop2.2033

Smith J, Kean S, Vauhkonen A, Elonen I, Campos Silva S, Pajari J, Cassar M, Martin-Deldago L, Zrubcova D & Salminen L. 2023. An integrative review of the continuing professional development needs for nurse educators. Nurse Education Today. doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105695

Vauhkonen A, Saaranen T, Cassar M, Camilleri M, Martin-Delgado L, Haycock-Stuart E, Solgajová A, Elonen I, Pasanen M, Virtanen H & Salminen L. 2024. Professional Competence, Personal Occupational Well-Being, and Mental Workload of Nurse Educators – A Cross-Sectional Study in Four European Countries. Nurse Education Today 133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.106069

We were all students once and we know what we liked about education, various methods, and teachers’ approaches and attitudes. As teachers, we use this experience and knowledge whether we realise it or not. In addition to the formal and widely used teaching strategies, we often act intuitively using our own ideas, techniques, and strategies When we share this information and when we say things aloud, we realise that other teachers use similar ideas, techniques, and strategies and adapt them to new situations. Together we can develop them, give them names, and thus make them part of formal education. One sentence activates another, which makes us see things in new perspectives. New ideas occur, and changes are made because everything is constantly in motion. Despite or thanks to the spatial distance and cultural differences, we produce better ways and solutions in our mission to improve nurse educator education, and thus care for patients.

This suggests the importance of collaboration between teachers, nurses, and scientists locally, nationally, and internationally. International collaboration in this project includes participation in classes, group meeting, workshops, seminars, and conferences. Both face-to-face and online meetings allow sharing the ideas, motivations, experiences, rationale, study results, strengths and limitations, and challenges and suggestions for the future. Various backgrounds of the participants are a great asset and enrichment for the development of ideas and achieving common goals.

Furthermore, international collaboration is important because health-related beliefs and needs may vary in patients who come from different backgrounds, cultures, or countries. The project activities, such as designing teaching plans, problem solving, writing papers, and exploring other issues draw attention also to those particularities.

Proximity means nearness or closeness in distance or time. We have become close not only in time and (online) space but also in our eagerness to learn new things, broaden our horizons and improve nurse educator education through open cross-border interaction.

The authors of the blog are (from left to right):

Tomas Sollar, Andrea Solgajová, Ľuboslavá Pavelova and Dana Zrubcova from Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Slovakia.

“To make the invisible more visible to others, is after all, a major goal of the interpreter”

(Denzin 2010: 32).

A blog post from Susanne Kean. The University of Edinburgh.

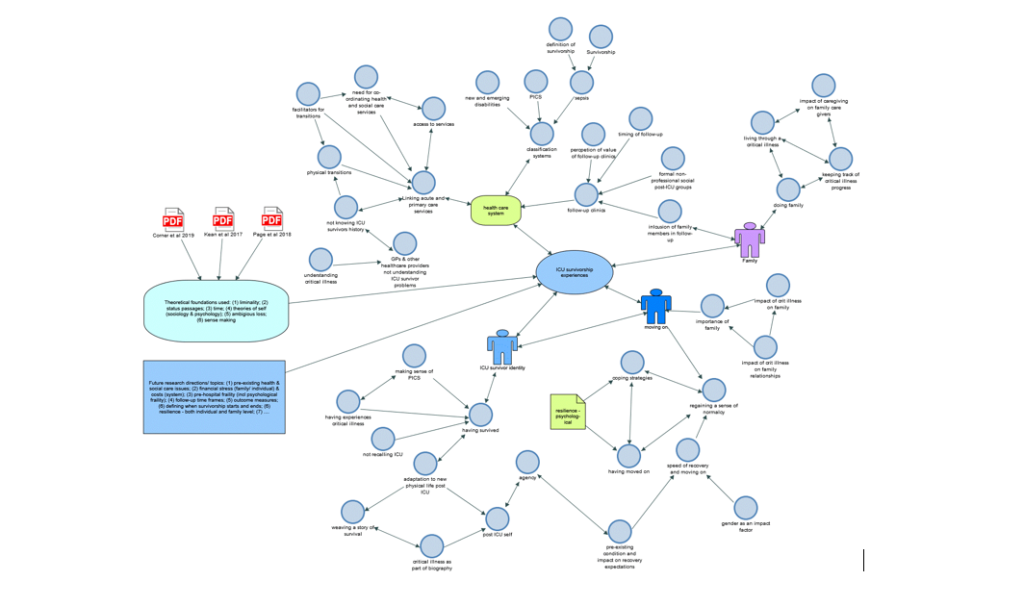

Mapping or modelling is one way of making the invisible more visible to the researcher and, eventually, to the reader of research. Mapping or modelling are data analysis techniques that come into play after the first round of analysis. These techniques can be used independent of methodology. To explain this technique, I will draw on Thematic Analysis (TA) and coding.

Coding, of course, is only one way of analysing data and not THE way. Coding originates in Grounded Theory but is today used well beyond this methodology. TA is an example where coding is used as an analytical device. A code, Saldaña (2021) proposes, “is most often a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, saline, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data” (p5). In other words, it is shorthand for data content, and this could be a word or a line or a paragraph.

Now, coding is only the beginning of data analysis, and yes, coding is analysis. In conversations with others (and specifically research students), I often get the impression that coding is thought of as a mechanistic devise to somehow sort data. However, how we sort data demands thinking and analysis. Coffey and Atkinson capture this beautifully when they remind us that:

“First, coding links different segments or instances in the data. We bring those fragments of data together to create categories of data that we define as having some common property or element. The coding thus links all those data fragments to a particular idea or concept.

The important analytic work lies in establishing and thinking about such linkages, not in the mundane process of coding.

We use the data to think with, in order to generate ideas that are thoroughly and precisely related to our data. Coding can be thought about as a way of relating our data to our ideas about those data.

In practice, coding can be thought of as a range of approaches that aid organization, retrieval, and interpretation of data” (Coffey & Atkinson 1996:27).

Coding, and thus analysis of data, is an iterative process. I am a Grounded Theorist by training and background and so am very familiar with the cycles of coding from open coding to focused coding to developing categories and eventually one or two core categories. A core category is nothing more, or less, than the main story in a data set. Whether we call this a core category, or a theme is neither here nor there but simply a differed terminology depending on the approach one takes. In TA, this would be called a theme. My point here is that coding, and thus analysis, evolves from a descriptive level to an abstract level of analysis. I agree with Thorne (2020) when she highlights that “finding themes” is too often declared as the end product of analysis when in reality, this is reflects nothing more than “surface-level considerations” of any given data set. I am wary when I review articles where authors claim they found seven themes and 15 sub-themes. This more often than not indicates nothing more than a data analysis that stopped at this surface-level describing data but not analysing them.

Analysis, as Flick points out “can be oriented to various aims. The first such aim may be to describe a phenomenon. Or the analysis could focus on comparing several cases (individual or groups) and on what they have in common, or on the differences between them. The second aim may be to identify conditions on which such differences are based – which means looking for explanations for such differences. The third aim may be to develop a theory of the phenomenon under study from that analysis of empirical material” (Flick 2023:385, Italics in original).

There is, of course, nothing wrong with description and descriptive studies have their place. However, description remains on an inductive level of analysis, and this does not get us to themes. To truly develop themes, we need abduction as analytical process. It is this process that allows us to go beyond description to explanation and explore not only why somethings happens but also what is going on (Blaikie and Priest (2017).

One way of developing an analysis beyond descriptions is mapping for themes. This technique comes into paly after focused codes have been developed. So, not right at the beginning but at a stage where the analysist is thinking about the linkages between different codes and categories to develop themes. Saldaña (2021) describes different ways one can develop themes through mapping. He distinguished between (1) theming data categorically and (2) theming data phenomenologically. I usually have the first approach of developing themes in mind when using modelling or mapping as a technique. This approach to data analysis allows the analyst to go beyond the descriptive coding schemes and include theoretical ideas/ concepts as they apply to the data.

Here is an example where we used modelling in a systemtic review exploring intensive care survivorship experiences.

At this stage of the analysis, we were thinking about the linkages and hierarchies of theoretical concepts in our data set. Software packages, like NVivo, allow models to be “active” models, meaning one can play around with hierarchies and think through linkages with every change. Mapping alongside the developing analysis also functions as an audit trail of the data analysis and provides a structure for writing up at a later stage.

Analysis always requires the interaction with data, and this process of modeling allows the researcher to think theoretically about the data as well as deriving any ideas from the data because, as Atkinson (2015) argues “the end-point of analysis is not a knitting -together of coded themes” (p 62). It is this process that allows us to go beyond description to explanation and the process that too often is missing in much of qualitative work in nursing (Thorne 2020, Atkinson 2015).

In summary, mapping and modeling are data analysis techniques that are useful in developing analysis beyond description. These techniques help analysts to think through linkages of codes and hence the interpretation of data.

References:

Atkinson P (2015) For Ethnography, SAGE, London

Blaikie, N & Priest, J (2017) Social research – paradigms in action, polity

Coffey A & Atkinson P (1996) Making sense of qualitative data, SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Denzin N (2010) The qualitative manifesto. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek

Flick U (2023) An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 7th edition, SAGE, Los Angeles

Saldaña J (2021) The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 4th edition, SAGE, Los Angeles Thorne S (2020) Beyond theming: making qualitative studies count (editorial), Nursing Inquiry, 27: e12343, doi.org/10.1111/nin.12343

Nowadays knowledge and experience are considered to be significant assets for sustainable success of projects. Sharing them properly through appropriate examples, cases, and justification of successes or failures offers better estimation of the project efforts among the stakeholders.

The Department of Nursing, Faculty of Social Sciences and Health Care, Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Slovakia, organised a two-day International Symposium “Nursing of the 21st Century in the Process of Changes 2022” on 8 and 9 September 2022. The meeting of experts from the universities in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia brought many interesting and stimulating speeches focused on research findings and linking theory with practice.

On behalf of all the participants of the New Agenda for Nurse Educator Education in Europe Project, Andrea Solgajová, Dana Zrubcová and Ľuboslava Pavelová informed the professionals on the nature, structure and implementation of the project intentions. We clarified the Project evidence-based recommendations for health policy makers of all the European countries and the EHEA countries. We discussed on nurse educator education and possibilities of enhancing educators’ knowledge, skills and professionalism.

There was the fruitful discussion about education for nursing students and their equal possibilities for high-quality education in Europe. The attention was also drawn to the content and course of education in the five Project modules.

Sharing the Project experience and achieved knowledge gives a possibility for new collaborations and to become more efficient in the development of the field of nursing internationally. Therefore, it is important to share experiences, best practice, opinions and ideas with project managers.

All the discussion participants recognised the importance of developing pedagogical competence and enhancement of collaboration in educator education and training in the EU. They recognised the Project as an effective education programme for nurse educators reflecting on current changes in health care.

Authors: Ľuboslava Pavelová, Andrea Solgajová, Dana Zrubcová and Tomas Sollar from Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra.

The 8th NETNEP conference was organized in the end of October 2022, in Sitges, Spain with the theme “From education to impact: Transforming nursing and midwifery education”. From the beginning the NETNEP conference aimed to facilitate the sharing of knowledge and experience of nursing, midwifery and healthcare education worldwide and NETNEP 2022 continues this aim by encouraging the sharing of research and practice of nursing, midwifery and healthcare education. Moreover, the conference gave the possibility to discuss with colleagues and network. Especially, in the poster hall, there were a lot of interesting discussions.

This year there were more than 800 delegates. The programme consisted of keynote presentations, oral and poster presentations – including the Rapid-5 short oral communications and also some workshops. The topics of the conference was: 1) Teaching & assessment, 2) Learning in practice – Clinical education, 3) New technologies, simulation and social media in teaching and practice, 4) Curriculum innovation & development, 5) Evidence and educational discourse, 6) Research, scholarship and evaluation and 7) Professional development & leadership.

The first keynote speaker Dr Hester Klopper from the Stellenbosch University in South Africa spoke the Global trends and transformation: Implications for nursing and midwifery education. She brought up in developing the nursing and midwifery curricula the importance of interprofessional and transdisciplinary, collaboration, social justice for health, pandemic response and skills se for the future, both hard and soft skills.

Most of the presentations concerned the nursing education, the students experience of education, their learning outcomes and use of different kind of teaching methods in teaching. New technologies and digital pedagogy were well presented. Much less was educator education, role and competence featured. Therefore, our New Nurse Educator -project was a good addition for this topic with total of four posters and two oral presentations.

As a summary can be said that the conference was organized very nicely, the programme was good, there were a lot of different kind of presentations. The quality of the presentations was varying as it always is in this kind of large conferences. Sitges, the small town in Catalunya was an exquisite place and sun was shining all the time. Already waiting for the next NETNEP conference, even the topics, the place and the dates are not yet informed.

Thankyou Sitges, you were good to us!

Building Bridges

Blog by Ľuboslava Pavelová, Andrea Solgajová, Dana Zrubcová

There are seven continents, almost two hundred countries, more than seven thousand languages, and almost eight billion people on our planet. There are so many differences in this world – abilities, past, nationalities, love, climate, music, beliefs, political situation, accents, moods, religions, technology, customs, foods, clothes, health, nature, experiences, infrastructure, feelings, values, traditions, colours, temptations, education, personalities, symbols, hopes, characteristics, art, social situation, lifestyles, health care, social classes, ambitions, services, professions, currencies, problems, architecture, families, transport, illnesses, behaviours, dreams, coping mechanisms, sports, attitudes, security, natural resources, day-to-day life, and many more.

Differences do not have to mean barriers. We do not need to change other people. Finding ways to each other is what matters. It does not take a lot – we just need to be open-minded, respect each other, and build more bridges and tear down walls.

Diversity makes the world and each of us unique. Diversity and uniqueness are enriching as they make our lives more interesting and colourful, and they enhance tolerance towards other people and their beliefs. We can learn from each other and make our lives more meaningful.

Health care, more than other areas of life, keeps showing us that we are all human beings, we are all the same in our essence. Taking care of and communicating with people from various backgrounds may be challenging – the differences in languages and health-related customs, beliefs and attitudes may cause many problems and treatment may become more time consuming. However, as nurses, we always try to find out what we have in common with other people, and how to help people who are ill, weak, helpless, different in their suffering or life stories but also the same in their needs.

Education is one of the best ways to communicate and understand other people.

Nurse education prepares nurses for their duties as nursing care professionals.

Nurse educator education is a bridge between two major professions – nursing and teaching. It includes even more bridges to other professions whose common goal is to help those in need.

Each and every day, the situation in the world reminds us that education is extremely important and, as a living organism, develops and depends on each of its smallest parts – each of us.

The world is great in its diversity. So, let’s build more bridges to make it a better and happier place. We are all in it together.

“Our dreams of being better teachers are coming true and we thank you for your support and this opportunity.”

One can hardly wish for a higher reward than this kind of feedback from a student.

Evidence-based practice is already a familiar concept in nursing, and in education it is clear, that the content that is being taught, ought to be evidence-based. But evidence-based teaching is more, than content. Nurse educators need evidence-based knowledge in designing curriculum and selecting appropriate teaching and learning methods (Kalb et al., 2015). Evidence-based teaching can be seen as a decision-making process including the best available evidence about teaching and learning, and also expertise and judgment of the educator and the preferences and goals of the learners (Oermann, 2021). Furthermore, nurse educators need to be able to facilitate the future nurses in their profession, so that they are familiar with processes and implementation of evidence-based practice (Kajander-Unkuri et al., 2020).

Evidence-based Teaching study unit is the fourth study unit of Empowering the nurse educators’ in the changing world (ENEC) study programme. The study programme is aimed for nurse educator candidates and educators in Europe. The study programme can be utilised as Continuous professional development (CPD) activity or as a part of degree education in nursing and health sciences educator education. University of Eastern Finland has been the coordinator and main organiser of this study unit.

Evidence-based teaching study unit was organized as hybrid implementation. Majority of the activities were conducted online, but the students of the study unit performed a teacher training in one of the partner universities in international groups. Due to pandemic situation and the war in Ukraine, that has especially affected the neighbouring countries, the students were allowed to participate the teacher training also online. In addition to teacher evaluations, the study programme utilised both self- and peer evaluation as one of the learning methods, as they both can be even more beneficial than educator evaluation, even though the self- and peer evaluation don’t always concur (Iglesias Pérez et al., 2022). The students also received feedback from the students who they were teaching during their teacher training sessions.

As in the beginning of this blog, students experienced the teacher training beneficial to them. Furthermore, the partners hosting the teacher trainees, also had a good experience with the international students:

“The students managed to engage colleagues in a stimulating discussion about differences and similarities between the countries and I believe that everyone learned a lot. I was very impressed about their well-planned and structured lesson.”

The impact of visiting students went beyond the teacher training they had during the training week. They met with the faculty and students at the universities, universities of applied sciences, colleges, Hospital districts, vocational institutes and many other collaborators and have made great impression on the hosts of the training.

“Just as feedback, your Erasmus students are wonderful. They’ve been well prepared and have spent lots of time considering how to approach the teaching sessions. They deliver well and have helped each other.”

“I loved their use of a hospital soundtrack – beeping, phones ringing – to help explain how stressful the backdrop is in a hospital. That worked really well. They used clever QR code links to mentimeter and tried to engage a slightly stubborn year 1-2 audience. I have to learn how to do that!”

The evidence based teaching study unit was a very intensive yet beneficial study unit. Both teachers and students had immense opportunities to share experiences and learn from each other, beyond the content of the study unit. All of the hosts arranged some extra curricular activities and possibilities to learn about the culture and quisine of the hosting country.

On behalf of teams UTU and UEF and the whole New Nurse Educator -project, we thank all our collaborators, faculty and students for a great study unit.

Faculty and students of the Nursing Department and Physiotherapy Department in the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya

Nursing, physiotherapist and medical staff from the Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya-Grupo Quironsalud, in special Sara Cano and Montserrat Granados.

Staff of the Faculty Hospital in Nitra

Staff and students from Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra

Ms. Lorraine Close, Ms. Ally Lai and Dr. Sarah Rhynas from The University of Edinburgh.

Students and staff of The University of Edinburgh

Ms Carmen D’Amato, Director of Nursing, Ms. Bernice Zarb and Mr. Mathew Abela, Mater Dei Hospital, Malta.

Students and staff of University of Malta

Staff and students of the Institute of Health and Nursing Science at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Students and staff from Savonia University of Applied Sciences

Clinical nurse educators and staff from Kuopio University Hospital

Mika Alhonkoski and the students in practical nursing, Turku Vocational Institute

Öhberg Isa and the student nurses, Turku University of Applied Sciences

Merja Nummelin, the coordinator of clinical nurse educators and the clinical nurse educators from Turku University Hospital

Karolina Olin and Karoliina Marjaniemi, County Patient Safety Control Center at Turku University Hospital

Camilla Strandell-Laine, Novia University of Applied Sciences

Professor Helena Leino-Kilpi, Assistant Professor Anna Axelin and the students of Future health and Technology from University of Turku

And on behalf of all the staff and students of the New Nurse Educator -project, we want to thank Anneli Vauhkonen, Terhi Saaranen and Juha Pajari from University of Eastern Finland for organizing the study unit Evidence Based Teaching.

Authors are:

Imane Elonen, MNSc, Doctoral researcher, University of Turku

Anneli Vauhkonen, MNSc, Doctoral researcher, University of Eastern Finland

References

Iglesias Pérez, M. C., Vidal-Puga, J., & Pino Juste, M. R. (2022). The role of self and peer assessment in Higher Education. Studies in Higher Education, 47(3), 683-692.

Kajander-Unkuri S., Melender H-L., Kanerva A-M., Korhonen T., Suikkanen A. & Silén-Lipponen M. (2020) Sairaanhoitajan osaamisvaatimukset – suomalainen koulutus 2020-luvulle. Teoksessa: Silén-Lipponen M. & Korhonen T. (toim.). Osaamisen ja arvioinnin yhtenäistäminen sairaanhoitajakoulutuksessa – YleSHarviointi-hanke. Kuopio: Savonia-ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisusarja 5/2020, 22-30. https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/347289

Kalb K.A., O’Conner-Von S., Brockway C., Rierson C.L. & Sendelbach S. (2015) Evidence-based teaching practice in nursing education: faculty perspectives and practices. Nursing Education Perspectives 36(4), 212-219.

Studying in an international group

Blog post by Anndra Parviainen, University of Eastern Finland

My love and passion to nursing education ignite me to enrol in a comprehensive nurse educator education program offered by the Erasmus+ funded New Nurse Educator project – Empowering the Nurse Educators in the Changing World. The study program is aimed for nurse educator candidates to prepare them for their work as nurse educators and to nurse educators to help them maintain their professional competence as nurse educators.

Issues in Future Nurse Education (5ECTS) is one of the study units of this program. Participants of the course were from different countries like Germany, Finland, Malta, Spain, Slovakia, and UK. Coming from Philippines, I realized that even though we came from different countries with different health care systems and culture, we are the same when it comes to the global health challenges and future issues in nursing education that we faced in this time. The most exciting part of the study unit was the intensive collaborative group project on integrating contemporary and future issues in nurse and health professions education in curricula in higher education.

Students were encouraged to form groups and come up with a topic for their collaborative group project during the first online session. The topics of the group projects were: interprofessional education, leadership, competence-based education, and mental health. The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity highlighted the need to build a broader coalition to increase awareness of nurses’ ability to play a full role in health professions practice, education, collaboration, and leadership; the need to continue to make promoting diversity in the nursing workforce a priority; and the need for better data with which to assess and drive progress (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2021).

My experience working in an international team of learners is very rewarding. I admire the respectful atmosphere during the whole study course. There might be some misunderstandings due to miscommunications and language barrier, but at the end of the day, together we find solutions by communicating and clarifying things that seems to be unclear in a respectful and peaceful way. The uniqueness of every learner and wide array of expertise makes the learning process exciting and enjoyable.

Research evidence shows that collaborative group learning as pedagogical educational approach is effective for preparing students to work collaboratively with one another (Prichard et al., 2006; Sáiz-Manzanares et al., 2020). The impact of working in an international team of learners to my learning have improved my interpersonal skills and communication skills. Our mentors have shown us good example on how to facilitate collaborative learning and this skill is important to me personally as a nurse educator as I can use this approach in facilitating learning to my students. In conclusion, I can say that the course has empowered nurse educators like me by acquiring the updated knowledge and skills regarding the process of learning from multicultural group.

References

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. (2021). The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982

Prichard, J. S., Bizo, L. A., & Stratford, R. J. (2006). The educational impact of team-skills training: Preparing students to work in groups. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(1), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709904X24564

Sáiz-Manzanares, M. C., Escolar-Llamazares, M. C., & Arnaiz González, Á. (2020). Effectiveness of Blended Learning in Nursing Education. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(5), 1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051589

The author of this blog is Anndra Parviainen, a PhD-student form University of Eastern Finland (UEF), Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Nursing Sciences, Kuopio Campus Finland. Originally, she is from Philippines. She came to Finland to advance her nursing career year 2015. At present, she works as Project Researcher in UEF and as Global Education Designer. Issues related to precision medicine, personalized care, and the integration of genomics in nursing education are her main areas of interest and are also related to her dissertation.

Just having fun in EleneIP!

Author:

The author of this blog is Johanna Kero, a PhD-student form Tampere University(current) and University of Turku (former). She works as a nurse lecturer in Satakunta University of Applied Science. Her interest is to pilottest different digital learning environments and applications with students. Her motto is: pilots never fail!

Empowering Learning Environments in Nursing Education (EleneIP) –course is a modern and innovative study unit for nurse educators and educator candidates. The study unit originates from an Erasmus+ project over a decade ago (Salminen et al. 2016). Then a two-week intensive face-to-face study unit has been modified and modernized into a hybrid study unit consisting of both interactive and individual online working and a face-to-face intensive week.

The constantly renewing study unit is well established and has gained great popularity among both Finnish and international students. The signature features of the study unit are the warm and inviting international atmosphere and solid evidence base that is constantly reviewed, to maintain high quality and timely research evidence. ELENE-IP gives an opportunity not only to meet international students and nurse lecturers but also new ideas how to advance nurse education. During the course participants have an opportunity to test many digital learning environments and applications such as Instagram, Reddit, Mentimeter, Powtoon, What’sApp and many others.

As a doctoral candidate of University of Turku, I had a great opportunity to be a part of international EleneIP-course in a role of tutor in autumn 2021. The year earlier, Covid-19 pandemic forced the ELENE-IP to be organized online but it didn’t matter. It is known that virtual training workshops can provide numerous benefits to learners (Smith et al. 2021) and I agree since the use of digital applications mentioned earlier, even simulations, worked very well as an online workshops.

In autumn 2021, the EleneIP had biggest number of participants than ever before, about 40. Participants represented 10 different nationalities. What made this year special, was the number of international students, which was boosted by the Erasmus+ funded New Nurse Educator project participation with additional 15 international students. In addition, for the very first time, the intensive week was arranged as a hybrid-model as well, meaning that some of the students completed the study unit fully online whereas others were able to enjoy the hybrid model with face-to-face intensive week. Even though a minority of participants were participating online, the distance-accessibility (Smith et al. 2021) was deemed essential for this international course at this time of pandemic. Online learning can be highly satisfying, increase knowledge and improve engagement to the subject (Kim et al. 2021). Furthermore, both hybrid and online studies can be equally good for students (Ainslie et al. 2021). The online students in ELENE-IP intensive week, were able to participate all education and group works, but they felt occasionally forgotten and invisible. This is something all educators need to remember, when utilizing simultaneous hybrid education. Inclusion of distance students may require just a little bit extra attention but it is worth your while.

As a summary, in my opinion after EleneIP-intensive week my knowledge and expertise of digital teaching increased both in class room and online. If you feel that you need more competence of digital learning and teaching, EleneIP-course is the answer: you learn by doing from both point of views of learner and teacher.

References:

Ainslie, M., Capozzoli, M., & Bragdon, C. (2021). Efficacy of distant curricular models: Comparing hybrid versus online with residency outcomes in nurse practitioner education. Nurse education today, 107, 105146.

Kim S-Y, Kim S-J & Lee S-H. 2021. Effects of Online Learning on Nursing Students in South Korea during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(16): 8506

Salminen L, Gustafsson ML, Vilen L, Fuster P, Istomina N & Papastavrou E. 2016. Nurse teacher candidates learned to use social media during the international teacher training course. Nurse Education Today. 36, 354–359.

Smith T.S., Holland A.C., White T., Combs B., Watts P. & Moss J. 2021. A Distance Accessible Education Model: Teaching Skills to Nurse Practitioners. The Journal of Nurse Practitioners 17: 999-1003